هيمنة هوليوود على السينما العالمية أمر لا يجادل فيه الآن سوى نفر أقل من القليل.

وهي هيمنة ترجع ارهاصاتها إلى ما قبل الحرب العالمية الأولى بقليل، وعصر السلام الجميل على وشك الرحيل.

ولعل أول أرهاصة لها “ميلاد أمة” أول فيلم يشاهده الرئيس الأمريكى “ويلسون” في البيت الأبيض فيعبر عن دهشته واعجابه بروعة الأطياف التى مرت أمام عينيه قائلاً أنه رأى “التاريخ مكتوباً بالبرق”.

ومن بين الارهاصات ظهور نظام النجوم ونجاحه نجاحاً منقطع النظير بحيث أصبح ممثلون كشارلي شابلن “وماري بيكفورد” و”دوجلاس فيربانكس” ــ كانوا إلى عهد قريب مغمورين ــ فجأة من المشاهير، بسحر الصورة المتحركة تجري أسماؤهم على كل لسان، لهم عشاق فى كل مكان.

الصمت والكلام

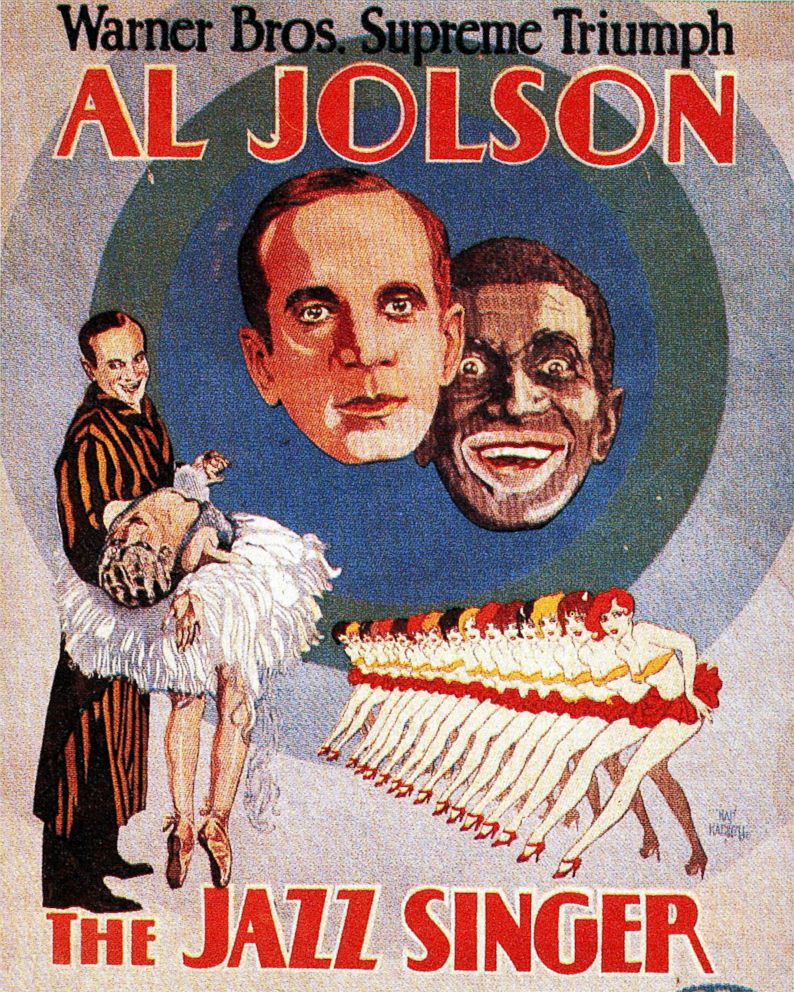

وبعد منتصف عقد العشرينات بعام وبضع عام ــ انفردت السينما الأمريكية بالكلام، يوم السادس من أكتوبر 1927، ففى ذلك اليوم تحقق ما كان يحلم به السينمائيون منذ أن تحركت الأطياف 1895 عندما نطقت السينما للمرة الأولى في الفيلم الأمريكى “مغني الجاز”.

وبدءًا منه والأفلام لا تكف عن الكلام والصوت يرقى فيها على الدوام.

وفي هذه الاثناء ظهرت فى المانيا السينما المسماة بالتعبيرية.

وفي روسيا البلشيفية، سينما اتسمت بالواقعية والاشتراكية.

وتحت تأثير الديكتاتورية في هذين البلدين الكبيرين سرعان ما تدهورت السينما، فأصبحت بوق دعاية مباشرة، فجة، لا هم لها إلا تمجيد عبادة الزعيم هتلر في المانيا، والرفيق ستالين في روسيا.

حقا كانت أزمنة عصيبة لم يستفيد منها إلا مصنع الاحلام في هوليوود.

سر الهيمنة

فقد أتاحت له فرصة الهيمنة على السينما العالمية بأفلامه المتعددة الأنواع المشارك في إبداعها مخرجون موهبون بعضهم هارب من نير النازية.

وتلك الهيمنة ترجع إلى عدة أسباب لعل أهمها:

أولاً: توافر حرية التعبير للسينمائين في الولايات المتحدة، دون زملائهم خارجها على امتداد العالم الفسيح.

ثانياً: السبق الأمريكى في الاختراع والاسراع بتطبيقه عملياً في جميع المجالات، وفي مقدمتها صناعة الأطياف.

ثالثاً: أزدهار نظام النجوم حتى أن شركة كبيرة مثل مترو جولدين ماير كانت تتفاخر على “شركات هوليوود الأخرى بأن نجومها أكثر عدداً من تلك التي في السماء!!”.

رابعاً: ابتداع الاوسكار، وحفل توزيع جوائزها سنوياً بدءًا من 1927، سنة انطلاق السينما من الصمت إلى الكلام.

والحق أن مبتدعي الأوسكار كانوا بعيدي النظر إلى حد كبير.

فعلى مر السنين أصبح لها شأن عظيم في الدعاية لمستحضرات هوليوود على امتداد العالم شرقاً وغرباً.

ويكفي في هذا الخصوص الدعاية التى تتحقق لصالح أفلام مصنع الأحلام بفضل الحفل السنوي الذي يُقام في الأيام الأخيرة من شهر مارس حيث يجري إعلان الجوائز وتوزيعها أمام حشد من مشاهير النجوم، يشاهده على الشاشات الصغيرة ألف متفرج أو يزيد، منهم من يراهن على فوز أو خسارة الأفلام المتنافسة والمشاركين في ابداعها بعزيز المدخرات.

وحفل الأوسكار يجري الاستعداد له في وقت مبكر والسنة على وشك الانتهاء، عندئذ يسرع المتنجون بعرض أفلامهم داخل الولايات المتحدة، ولو في دار واحدة، وذلك بأمل اكتساب حق الاشتراك بها فى مضمار المنافسة على الأوسكار.

وما أن ترحل السنة، وتنتهي أجازات أعياد الميلاد ورأس السنة الجديدة حتى يجتمع أعضاء اتحادات نقاد السينما فى أكثر من مدينة كبيرة للتداول في أمر الأفلام التى يرونها جديرة بالتقدير.

ولعل أعلى تلك الاتحادات مقاماً اتحاد نقاد نيويورك ولوس انجلس.

الكرة الذهبية

ومع ذلك فاتحاد الصحفيين الأجانب بلوس انجلس ــ وليس هذين الاتحادين ــ هو الذي يُعمل لجوائزه المسماة الكرة الذهبية ألف حساب لماذا؟

لانها تفتح للفائزين بها أبواب الأوسكار ومن هنا انتظار النجوم وصانعي الأفلام حفل توزيع الجوائز بفارغ الصبر. فالمؤكد ترشيح الفائزين بها فى ذلك الحفل للأوسكار.

وفي معظم الأحوال تكون، أى جائزة الأوسكار من نصيبهم فى نهاية المطاف.

ومصداقاً لذلك حظ الأفلام الفائزة بالكرة الذهبية من الأوسكار خلال الأعوام العشرة الأخيرة؛ ففيما عدا فيلمين فقط فازت جميع الأفلام الأخرى بالأوسكار.

الانتصار والاندحار

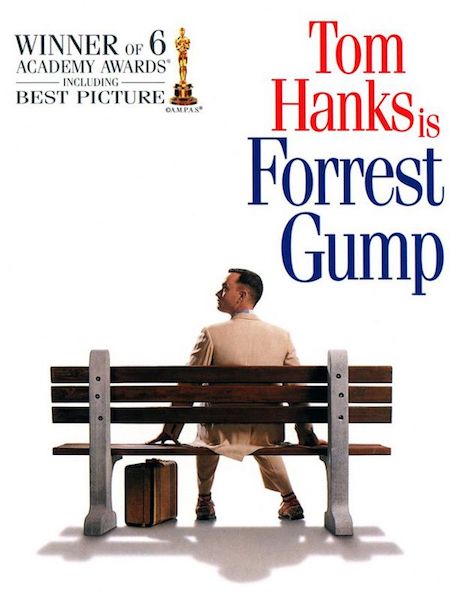

وعلى كُلٍ، فقبل أسابيع قليلة فاز “فورست جامب” بالكرة الذهبية باعتباره أحسن فيلم ويلعب الدور الرئيسى فيه “توم هانكس”.

وعن أدائه لذلك الدور فاز هو الآخر بالكرة كما فاز بها مخرج “روبرت زيميكيس” صاحب “الأرنب روجرز” و”العودة إلى المستقبل”.

ولا يضارع “فورست جامب” في عدد الكرات الذهبية الفائز بها أي فيلم آخر.

ففيلم “أدب رخيص” الذي كان منافساً خطيراً له لم يفز إلا بكرة واحدة وهي الكرة المخصصة للسناريو. والغريب أن يندحر هكذا أمام “فورست جامب”.

ووجه الاستغراب أنه قبل إعلان نتائج الكرة بأيام كان نقاد السينما في لوس انجلس قد اختاروا أحسن فيلم. ولم يكتفوا بذلك، بل جنحوا إلى منح الكرة إلى اثنين من مبدعيه، مخرجه “كوينتين تارانتينو” ونجمه “جون ترافولتا”. وشاركهم في تفضيل “تارانتينو” على “زيميكيس” المجلس القومي لعارضي الأفلام واتحاد نقاد السينما في نيويورك. وليس من شك أن كلا الفيلمين “فورست جامب” و”أدب رخيص” سيجري ترشيحه للأوسكار.

ملك الغابة

وأغلب الظن أنه سيكون من بين الأفلام المرشحة معها “الأسد ملك الغابة” الذي حقق ايرادات مذهلة في تفوق ايرادات “حديقة الديناصورات” بعد حين. كما فاز بالكرة الذهبية الخاصة بالأفلام الكوميدية أو الموسيقية، باعتباره من ذلك النوع من الأفلام، وذلك رغم أنه متأثر إلى حد كبير بمأساة هاملت أمير الدانمارك، للشاعر ويليم شكسبير!!.

توقعات لا نبوءات

وفي اعتقادي أن أوسكار أحسن فيلم ومخرج وممثل رئيسى، ستكون من نصيب “فورست جامب” ومخرجه “زيميكيس” ونجمه”هانكس”. ففضلاً عن فوز الثلاثة بالكرة فالفيلم حقق ايرادات فاقت كل التصورات هذا إلى أنه خال من ذلك العنف الدموي، وتلك الألفاظ البذيئة الزاخر بها “أدب رخيص” الفيلم المنافس له.

والأهم أن موضوعه مس وتراً حساساً فى الشعب الأمريكى، وخاصة الشرائح العليا من طبقته المتوسطة الواسعة للنفوذ، بحيث أصبح بفضله من الأفلام الأمريكية القليلة التى من كثرة الكلام عنها تحولت إلى رمز لحال أمريكا وأهلها. ومن بين تلك الأفلام أذكر “مولد أمة” و”أعناب الغضب” و”ذهب مع الريح” و”الأب الروحي” و”آى تي”.

الطيبة المجزية

والموضوع الذي نحن بازائه يعتمد على شخص واحد، هو البطل “فوريست جامب” ومن حوله أشخاص كثيرون لكل منهم مكانه واثره، أمه، رفاقة في المدرسة، وحبيبته، الفيس برسلي، جون ليتون حاكم الولاية “جورج دالاس”. المحاربون معه في فيتنام، الرؤساء كينيدى، جونسون ونيكسون.

والبطل “جامب” أقل ذكاء من المعتاد بل يكاد يكون معوقاً. ومع ذلك استطاع بفضل أولاً تمسكه بأهداب الفضائل والمبادئ التى لقنتها له أمه وهو صغير وثانياً قيامه بانجاز أية مهمة اسندت إليه على خير وجه، مهما كانت الصعاب، استطاع تجاوز جيمع العقبات، ولا اقول صنع المعجزات.

وها هو ذا متفوق حتى على هؤلاء المقول بأنهم أكثر منه فطنة وذكاء. فقد أصبح ثرياً، وفاز بمحبوبته، ومنها أنجب طفلاً رائعاً.

ولنجاحه على هذا الوجه، رغم كل المعوقات أصبح “جامب” تجسيداً لتوجسات ومخاوف الأمريكيين المتولدة عن فقدانهم الثقة بأنفسهم لظنهم أنهم ليسوا على مستوى التحديات وما فشلهم إلا عقاباً يستحقونه عما اقترفوه في حق أنفسهم.

ومن هنا اعتبارهم انتصار”جامب” وكأنه انتصارهم.

فجامب والحق يقال لا يعدو أن يكون إعادة بناء عبقري من قبل “زيميكيس” وهو من مدرسة ستيفن سبيلبرج” لخرافة أمريكا التى أصبحت هشيماً في أثناء عقد الستينات. فأمريكا حسب “جامب” بلد متحرر من الطبقات بلا تاريخ عنصري بدون ماض أبيد فيه الهنود الحمر.

بلد لا يعاني سكانه من استلاب الأشياء “فجامب” يمشي لابساً ثوب الحياة، ببراءة وطيبة، بهما يخلص الجميع من عواقب الآثام في بلد تتحقق فيه كل الأحلام.